We’ve been protecting Earth’s land for 100 years. We’re finally starting to protect its oceans

By Brady Dennis and Juliet Eilperin

NOTE: This article originally appeared in the Washington Post on September 14, 2016

A decade ago, only a tiny fraction of the world’s oceans had been protected from overfishing and other environmental threats. The United States had scores of national parks and other landmarks. Other countries had safeguarded cultural, historical and natural treasures. But for the oceans, such efforts remained in their infancy.

“Ocean conservation was an afterthought,” said Matt Rand, who directs the Global Ocean Legacy project for the Pew Charitable Trusts. “When you looked around the world a decade ago, very little investment was going into the conservation of ocean ecosystems.”

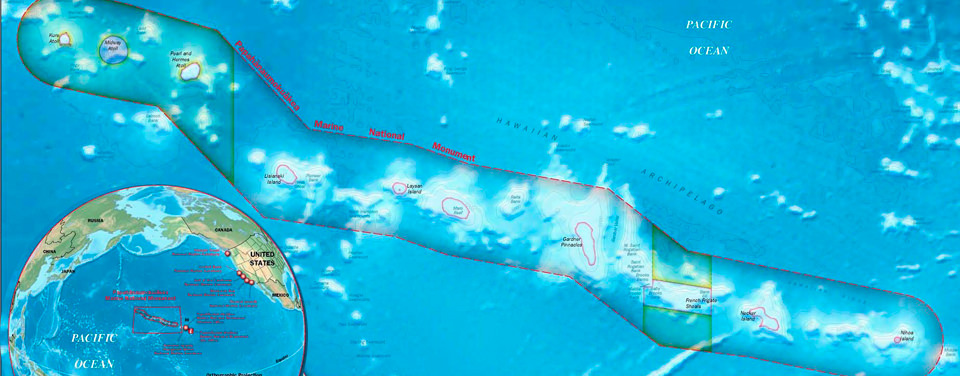

A key example of how that began to change came in 2006, when President George W. Bush designated an island chain spanning nearly 1,400 miles of the Pacific northwest of Hawaii as a national monument. Last month, President Obama expanded the Papahānaumokuākea (pronounced “Papa-HA-now-moh-koo-AH-kay-ah”) Marine National Monument to 582,578 square miles of land and sea, creating the largest ecologically protected area on the planet.

As government leaders, scientists and environmental activists from around the world gather this week at the State Department for what has become an annual global conference on preserving the oceans, roughly 3 percent of the world’s oceans are now protected. That’s a far cry from the 30 to 40 percent that many scientists think will be necessary over the long term to maintain the sustainability of the seas that feed billions of people and employ millions of workers. But it’s exponentially more than only a few years ago.

“I’m thrilled with the progress we’ve made,” Secretary of State John F. Kerry, who engineered the first such gathering in 2014, said in an interview, even as he acknowledged that much more work lies ahead. “Through my years in the Senate, there had been great [nongovernmental] oceans advocates. … But I think it needed the force of an administration and a department like the State Department to say, ‘We’re not going to leave you out there on your own. This is our responsibility, too.’ “

The Obama administration’s embrace of the cause has emboldened ocean advocates and helped fuel a global push to set aside more protected areas.

“Right now, I’m more hugely hopeful for ocean conservation than I’ve ever been at any other time in my career,” said Janis Jones, president of the Ocean Conservancy, an environmental advocacy group. “There are more and more people invested in protecting the ocean.”

Those people include local advocates trying to protect marine species from threats that include plastic debris and the acidification underway as oceans absorb human-generated carbon emissions. But increasingly, it also includes high-level leaders in different parts of the globe.

Last year, for instance, the president of the tiny island country of Palau in the western Pacific Ocean pushed to create a marine reserve larger than the state of California. President Thomas Esang “Tommy” Remengesau Jr. signed a designation to keep 80 percent of its territorial waters from activities such as fishing and mining. About the same time, Chile created the largest marine reserve in the Americas off its coast called Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park. The area encompasses roughly 115,000 square miles — almost the size of Italy.

And last week, the presidents of Ecuador, Colombia and Costa Rica announced they would expand the marine protected areas under their jurisdiction to more than 83,000 square miles, creating a network of underwater “highways” that will allow wide-ranging species such as sea turtles and sharks more freedom to move without facing intense fishing pressure. Making the announcement, Ecuador President Rafael Correa noted his nation’s underwater territory is five times larger than its terrestrial one.

Aulani Wilhelm, vice president of Conservation International’s Oceans Center, said the push to protect large parts of the sea signals a cultural shift.

“Large-scale marine protected areas are the single largest driver for ocean protection right now,” said Wilhelm, who led the public process that resulted in President Bush creating the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in 2006. “It was a crazy idea back in 2000. And now it’s normal.”

Wilhelm, who served as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration superintendent of Papahānaumokuākea from June 2006 to July 2014, said protecting those areas required a shift in mindset among policymakers. Once they accepted the idea of places in the ocean as part of a country’s cultural and historic heritage, she said, it became easier to declare them off limits.

“Before, we thought about heritage as cathedrals or maybe Mount Kilimanjaro,” Wilhelm observed, “but not about wild oceans.”

There remains considerable local opposition to restricting fishing activities in parts of the sea, whether it’s more than a thousand miles from Honolulu or off the coast of New England.

Eric Reid, general manager at a fish processing plant in Point Judith, R.I., said in an interview that just because the reserve closes off a small fraction of the ocean does not soften the economic impact on communities that fish there.

“If the state of Connecticut was turned into a monument and there was no economic activity whatsoever, or hit by a meteor or vaporized, the spin that could be used is it’s only 2 percent of the States,” Reid said. “But the people of Connecticut would be pretty uptight.”

A group of marine biologists and conservationists decided more than a decade ago to spur an intentional competition among heads of state in which leaders would vie for the mantle of designating the largest marine reserve on Earth. When Bush invoked the 1906 Antiquities Act to protect the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in 2006, it ranked as the world’s largest protected area, but by earlier this year it had slipped to 10th in the rankings. With its recent expansion, it reclaimed the No. 1 spot.

Advocates have appealed personally to heads of state — and their spouses — to grant these safeguards. Two wildlife photographers, David Liittschwager and Susan Middleton, spent much of 2003 and 2004 documenting marine and terrestrial species on the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and in the fall of 2005 the then-head of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, James L. Connaughton, gave their book “Archipelago” to first lady Laura Bush. The first lady, an avid birder, became a passionate advocate for creation of the monument and traveled there in 2007.

At times, scientists have even taken leaders underwater to view potential sites for protection. National Geographic explorer-in-residence Enric Sala went in a remotely operated underwater vehicle piloted by the president of Gabon to survey that nation’s offshore resources, and in 2014 President Ali Bongo Ondimba created a series of marine parks covering 18,000 square miles — 23 percent of the waters under Gabon’s jurisdiction.

“I saw that myself diving in the remote and unfished southern Line Islands in 2009,” he said. “These islands were hit by the strong El Niño of 1997-98, but 10 years later the corals looked pristine and healthy, as though that warming event never happened.”

Historically it has been difficult to get momentum behind ocean conservation in part because so much of the ocean is considered international high seas, and no one leader or one country can decide to protect it. Sala said this is the area that policymakers need to eye next.

“If nobody owns or is responsible for a patch of the ocean, it makes it much harder to create the coalition that’s necessary and the authority that’s necessary to move that ocean space into conservation,” Jones said. “It’s really hard, because the lines are not clear.”

She said that treating the oceans as a common space has hindered the world’s ability to safeguard them, and only in recent hears have nations made more concrete efforts to work together to grapple with which areas deserve protection.

“Continuing to treat the ocean just as a global commons is really ruinous for us all,” she said. “When everybody is responsible, nobody is responsible.”

Still, most experts said, many citizens in the United States and abroad have a hard time understanding the need for marine protected areas.

“People get parks on land. They don’t really get parks in the ocean. Not just green parks, but blue parks,” said Jane Lubchenco, who served as head of NOAA during Obama’s first term. “A hundred years ago it was set in motion a movement to protect special places on land. Now is the time to think about protecting special places in the ocean.”