Cuyahoga Valley park seeking scientists, volunteers for May 20-21 2016 BioBlitz

[Editors Note: this article originally appeared on ohio.com on April 25, 2016]

By Bob Downing

Beacon Journal staff writer

The Cuyahoga Valley National Park is preparing to inventory its flora and fauna on May 20-21, and it needs lots of help.

More than 80 local scientists and 1,200 volunteers are expected to participate in the park’s 24-hour BioBlitz to count plants, aquatic insects, amphibians, bats, birds, fish, fungi, insects, lichens, mollusks, reptiles and spiders.

Scientists will lead groups of community participants on surveys at locations throughout the park to create a snapshot of the park’s plants and animals.

The event officially begins at noon May 20, a Friday, and ends at noon May 21, a Saturday, in the 33,000-acre federal park between Akron and Cleveland.

But 500 school-age children from Northeast Ohio have been invited to join in the count on Friday morning in the park.

In addition, the park will stage a Biodiversity Festival beginning at 11 a.m. May 20 and 9 a.m. May 21 at the park’s Howe Meadow with hands-on science, music, arts and crafts vendors, and food.

On May 20, the festival will run until 6 p.m., with additional night hikes, bat viewing and astronomy sessions. On May 21, it will last until 2 p.m.

Local singer/songwriter Alex Bevan and gospel/jazz/fusion band the Funkyard Experiment will perform from 6 to 8 p.m. May 20 at the meadow off Riverview Road in Cuyahoga Falls.

Volunteers need some expertise to help on surveys but no special experience is needed to help with the two-day festival for families.

The Cuyahoga Valley’s BioBlitz is one of 123 across the country being staged by the National Park Service to mark its 100th anniversary. The initiative will provide a snapshot of the park system’s biodiversity through citizen science.

The national event is being co-hosted by the National Geographic Society, with results being disclosed on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

“Biodiversity refers to the variety of life on our planet,” said Jennie Vasarhelyi, chief of interpretation, education and visitor services for the Cuyahoga Valley park. “The value of biodiversity is fundamental to life as we know it on Earth. Wild species are part of natural systems that regulate climate, air quality, and cycles of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, mineral elements and water.”

Such surveys provide park managers with a key way to understand the health of the natural environment and a way to monitor change, she said.

This year’s survey could show a boost in fish and insects in the now-cleaner Cuyahoga River and it may show a decline in cave-dwelling bats that have been hit by the fatal white-nose syndrome, she said.

It is the first time that such an event has been staged in the Cuyahoga Valley, although Summit Metro Parks has held similar events in the past at the Gorge and Cascade Valley metro parks and Liberty Park. The Western Reserve Land Conservancy also held a similar event in 2015 at Haley’s Run in southeast Akron.

The Gorge event in 2006 recorded 385 species.

“BioBlitz is a fantastic opportunity to develop a better understanding of our park, and we’re collaborating extensively with schools, universities, government agencies and environmental, health and youth organizations in planning and implementing it,” Vasarhelyi said.

Individual surveys will use the app iNaturalist to catalog living organisms.

Interested participants are encouraged to visit the local BioBlitz website at www.nps.gov/cuva/bioblitz.htm to view survey opportunities and sign up.

Participants can follow, share and retweet their experiences using Facebook (www.facebook.com/NatureNPS) and Twitter (@NatureNPS) with the hashtags #BioBlitz2016, #NPS100 and #FindYourPark.

http://www.ohio.com/news/local/cuyahoga-valley-park-seeking-scientists-volunteers-for-may-20-21-bioblitz-1.678558

Unnatural Selection What will it take to save the world’s reefs and forests?

[Editors Note: This article originally appreared in The New Yorker for the April 18, 2016 issue]

By Elizabeth Kolbert

Ruth Gates fell in love with the ocean while watching TV. When she was in elementary school, she would sit in front of “The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau,” mesmerized. The colors, the shapes, the diversity of survival strategies—life beneath the surface of the water seemed to her more spectacular than life above it. Without knowing much beyond what she’d learned from the series, she decided that she would become a marine biologist.

“Even though Cousteau was coming through the television, he unveiled the oceans in a way that nobody else had been able to,” she told me.

Gates, who is English, ended up studying at Newcastle University, where marine-science classes are taught against the backdrop of the North Sea. She took a course on corals and, once again, was dazzled. Her professor explained that corals, which are tiny animals, had even tinier plants living inside their cells. Gates wondered how such an arrangement was possible. “I couldn’t quite get my head around the idea,” she said. In 1985, she moved to Jamaica to study the relationship between corals and their symbionts.

It was an exciting moment to be doing such work. New techniques in molecular biology were making it possible to look at life at its most intimate level. But it was also a disturbing time. Reefs in the Caribbean were dying. Some were being done in by development, others by overfishing or pollution. Two of the region’s dominant reef builders—staghorn coral and elkhorn coral—were being devastated by an ailment that became known as white-band disease. (Both are now classified as critically endangered.) Over the course of the nineteen-eighties, something like half of the Caribbean’s coral cover disappeared.

Gates continued her research at U.C.L.A. and then at the University of Hawaii. All the while, the outlook for reefs was growing grimmer. Climate change was pushing ocean temperatures beyond many species’ tolerance. In 1998, a so-called “bleaching event,” caused by very warm water, killed more than fifteen per cent of corals worldwide. Compounding the problem of rising temperatures were changes in ocean chemistry. Corals thrive in alkaline waters, but fossil-fuel emissions are making the seas more acidic. One team of researchers calculated that just a few more decades of emissions would lead coral reefs to “stop growing and begin dissolving.” Another group predicted that, by midcentury, visitors to places like the Great Barrier Reef will find nothing more than “rapidly eroding rubble banks.” Gates couldn’t even bring herself to go back to Jamaica; so much of what she loved about the place had been lost.

But Gates, by her own description, is a “glass half full” sort of person. She noticed that some reefs that had been given up for dead were bouncing back. These included reefs she knew intimately, in Hawaii. Even if only a fraction of the coral colonies survived, there seemed to be a chance for recovery.

In 2013, a foundation run by Microsoft’s co-founder Paul Allen announced a contest called the Ocean Challenge. Researchers were asked for plans to counter the effects of rapid change. Gates thought about the corals she’d seen perish and the ones she’d seen pull through. What if the qualities that made some corals hardier than others could be identified? Perhaps this information could be used to produce tougher varieties. Humans might, in this way, design reefs capable of withstanding human influence.

Gates laid out her thoughts in a two-thousand-word essay. The prize for the contest was ten thousand dollars—barely enough to keep a research lab in pipette tips. But after Gates won she was invited to submit a more detailed plan. Last summer, the foundation awarded her and a collaborator in Australia, Madeleine van Oppen, four million dollars to pursue the idea. In news stories about the award, the project was described as an attempt to create a “super coral.” Gates and her graduate students embraced the term; one of the students drew, as a sort of logo for the effort, a coral colony with a red “S” on what might, anthropocentrically, be called its chest. Around the time the award was announced, Gates was named the director of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology.

“A lot of people want to go back to something,” she told me at one point. “They think, If we just stop doing things, maybe the reef will come back to what it was.”

“Really, what I am is a futurist,” she said at another. “Our project is acknowledging that a future is coming where nature is no longer fully natural.”

The Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology occupies its own tiny island, known as Moku o Lo‘e, or, alternatively, Coconut Island. In the nineteen-thirties, Moku o Lo‘e was bought by an eccentric millionaire who fashioned it into an insular Xanadu. He installed a shark pond, a bowling alley, and a shooting gallery, and threw elaborate parties with guests like Shirley Temple and Amelia Earhart. After falling into decline, Moku o Lo‘e was rediscovered by Hollywood in the nineteen-sixties. TV producers used it in the opening sequence of “Gilligan’s Island.”

The first time I made the trip, it was a beautiful morning. I found Gates in a lab building that, from the outside, looks like a budget motel. She is fifty-four, with a round face, short brown hair, and a cheerfully blunt manner. Her office is spare and white; the only splash of color comes from a single painting—a seascape done on a piece of corrugated metal—that is the work of her partner, an artist and designer. The office looks out over the bay and, beyond it, to a dusty brown military base—Marine Corps Base Hawaii. (The base was bombed by the Japanese minutes before the attack on Pearl Harbor.)

Gates explained that Kaneohe Bay was the inspiration for the “super coral” project. For much of the twentieth century, it was used as a dump for sewage. By the nineteen-seventies, a majority of its reefs had collapsed. A sewage-diversion program led to a temporary recovery, but then invasive algae took over and the water turned into a murky soup.

In 2005, the state teamed up with the Nature Conservancy and the University of Hawaii to devise a contraption—basically, a barge equipped with giant vacuum hoses—to suck algae off the seabed. Gradually, the reefs revived. There are now more than fifty so-called “patch reefs” in the bay.

“Kaneohe Bay is a great example of a highly disturbed setting where individuals persisted,” Gates said. “If you think about the coral that survived, those are the most robust genotypes. So that means what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

In one set of experiments planned for the super-coral project, corals from Kaneohe Bay will be raised under the sorts of conditions marine creatures can expect to confront later this century. Some colonies will be bathed in warm water, others in water that’s been acidified, and still others in water that’s both warm and acidified. Those which do best will then be bred with one another, to see if the resulting offspring can do even better.

The power of selective breeding is all around us. Dogs, cats, cows, chickens, pigs—these are all the products of generations of careful propagation. But the super-coral project pushes into new territory. Already there’s a term for this sort of effort: assisted evolution.

“In the food supply, in our pets, you name it—everywhere you turn, selectively bred stuff appears,” Gates observed. “For some reason, in the framework of conservation—or an ecosystem that would be preserved by conservation—it seems like a radical idea. But it’s not like we’ve invented something new. It’s hilarious, really, when you think about it.”

Coral reefs are found in a band that circles the globe like a cummerbund. The band stretches from the Tropic of Cancer to the Tropic of Capricorn, though there are occasional reefs at higher latitudes—near Bermuda, for instance. The world’s largest reef, or really reef system, is the Great Barrier Reef, along the east coast of Australia. Reefs can be hundreds of feet tall and thousands of acres in area. Unlike the Great Wall of China, the Great Barrier Reef, which extends more than fourteen hundred miles, actually is visible from space.

The architects of these vast structures are difficult to see with the naked eye. Known infelicitously as polyps, individual corals are generally no more than a tenth of an inch or so across. They consist of a set of tentacles—either six or a multiple of six—arrayed around a central mouth. Corals can, in effect, clone themselves, so a typical polyp is surrounded by—and also attached to—thousands of other polyps that are genetically identical to it. Many are also hermaphrodites; they produce both eggs and sperm, which they release once a year, in the summertime after a full moon. The polyps live in a thin layer at the surface of a reef; the rest of the structure is essentially a boneyard, composed of the exoskeletons of countless coral generations.

One day, when I was hanging around Moku o Lo‘e, Gates offered to show me some polyps close up, through a state-of-the-art machine known as a laser scanning confocal microscope. The confocal is so elaborate that its many lenses and screens and beam splitters take up an entire room, and it’s so complicated that Gates had to call in a colleague—a molecular biologist named Amy Eggers—to run the thing.

“It’s a very dynamic little world,” Eggers observed. She upped the magnification, and I could make out the nematocysts, or stinging cells, at the tip of each tentacle. I could also see the corals’ minute plant symbionts. Under the laser, these showed up as bright-red dots, so that the polyps seemed to be glowing from within. As the polyps grew more active, I found myself investing them with little gelatinous personalities. One was waving particularly vigorously, as if trying to attract attention.

“You can imagine what happens when people step on them,” Eggers said. “I try not to think about that.”

Although corals can’t travel, they practice a highly effective version of hunting and gathering. Their nematocysts contain minute poisonous barbs; these they use to spear tiny planktonic prey, which they then stuff into their mouths. (Some corals also deploy nets made of mucus to nab their victims.) Meanwhile, their symbionts are producing sugars, via photosynthesis. The symbionts allow the bulk of these sugars to leak into the corals, an arrangement that, in human hunter-gatherer terms, might be compared to finding a tree that harvests and delivers its own fruit.

The efficiency of the symbiotic relationship is what makes reefs possible: the sugars released by their symbionts power the corals’ massive building projects. These projects, in turn, foster many other relationships—far more than marine biologists have been able to understand, or even catalogue.

Owing to Gates’s many administrative duties—in addition to running the marine-biology institute and her own lab, she’s the president of the International Society for Reef Studies—she spends a lot of her time in meetings. Whenever she has a chance, though, she jumps into the water. Another day when I was hanging around the island, Gates offered to take me with her.

It was a beautiful Hawaiian morning, but the bay, in midwinter, was cool enough that Gates recommended borrowing a wetsuit. The only suit in my size was an extra-thick one; getting into it made me empathize with any animal that’s ever been eaten alive by a boa. I finally managed to zip it, and Gates and I and two of her students set off in a fibreglass boat.

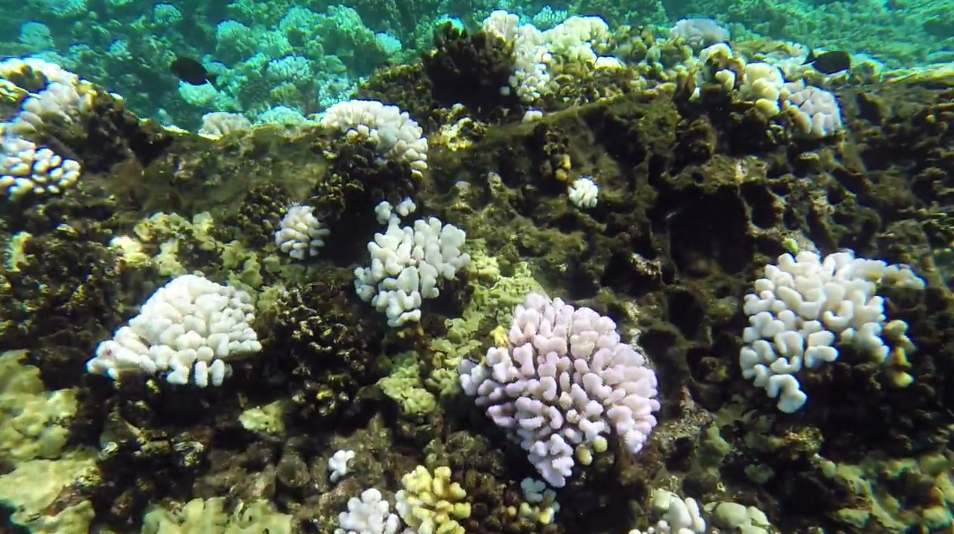

Our first stop was a reef nicknamed the Fringe. “Wow, there’s a lot of mortality,” Gates said as we anchored nearby. We put on masks and plopped into the water. When she got right up to the reef, Gates brightened.

“Wherever it’s still brown, it’s living tissue,” she told me. She pointed to a large colony of Montipora capitata, or rice coral, that was sporting a plastic tag. Much of it was covered with olive-colored algae, which looked like ratty shag carpet. But there were also lots of clumps of beige.

“It’s really heartening to see these reefs be so resilient,” Gates said.

We swam along. It was hard for me to tell what represented a sign of resilience and what didn’t, since I wasn’t entirely sure what I was looking at. Ribbons of bright orange, which I took to be a show of health, turned out to be the opposite—a species of invasive sponge, introduced from Australia. What struck me most about the reef was what was absent. Aside from an occasional—and spectacular—yellow tang, there were almost no fish. When I asked Gates about this, she said that it was the legacy of decades of overfishing. This was yet another problem for the corals, which depend on herbivores to keep down the algae that compete with them for space.

We pulled ourselves back onto the boat and motored on. We were in the flight path of the Marine base, and every few minutes a plane either landing or taking off screamed above us, trailing a cloud of black smoke.

The colors of a healthy reef are a sign of harmony. Polyps are transparent; it’s the microscopic plants living inside them that give them their ruddy hue. In very warm water, these tiny plants, which belong to the genus Symbiodinium, go into what might be described as photosynthetic overdrive. At a certain point, they produce so much oxygen that they threaten their hosts. To defend themselves, the polyps spit out (or slough off) their symbionts and turn white—hence the term bleaching.

In the summer of 2014, unusually high water temperatures in the Pacific caused widespread bleaching around Oahu. Reefs in Kaneohe Bay were particularly hard hit; an underwater video shot in the bay in October, 2014, shows colony after colony of stark white coral.

In the summer of 2015, water temperatures in Kaneohe Bay spiked again, by almost four degrees Fahrenheit. This time, the event was linked to a huge shape-shifting pool of warm water that became known as the Blob. Some of the bay’s corals hadn’t recovered from the first bleaching; many of those which had been rallying were once again laid low.

“At the height of the bleaching events in 2014 and 2015, we all went into the water and said, ‘Shit!’ ” Gates told me. “Two bleaching events in a row—that’s outrageous.”

Though Gates certainly hadn’t planned on back-to-back bleaching episodes when she proposed the super-coral project, in a perverse sort of way they turned out to be godsends. She wouldn’t have to design a test to find the toughest corals; the bay had performed that task for her, separating colonies that could withstand repeated bleaching from those which couldn’t.

In the bit of reef we were looking at in the Keyhole, this sorting process had played out with peculiar vividness. The three colonies, right next to one another, had been subject to the same water temperatures. What had distinguished the quick from the dead? Perhaps the colonies were, in some small but critical way, genetically distinct. Or perhaps the difference was epigenetic. Epigenetics is to genes what punctuation is to prose; epigenetic changes alter the way genes are expressed but leave the underlying code unaffected. Or the fault may lie not in the corals themselves but in their symbionts. There are dozens of strains of Symbiodinium, and different ones seem to be associated with different levels of heat tolerance.

Gates is hoping to explore all these possibilities. The aim of her project is not just to create a super coral but also to investigate whether corals that aren’t super can be trained, as it were, to do better. She believes that it may be possible to coax young corals to take up new symbionts, not unlike the way parents encourage children to make new friends. She also believes that exposure to moderately high temperatures induces epigenetic changes that can help corals withstand very high temperatures. If so, then she thinks it might be possible to “condition” reefs by dousing them with hot water. “Yes, it might be logistically quite difficult to do,” she told me. “But an engineer would be able to solve that problem in a heartbeat.

Coral reefs are often compared to cities, an analogy that captures both the variety and the density of life they support. The number of species that can be found on a small patch of healthy reef is probably greater than can be encountered in a similar amount of space anywhere else on Earth, including the Amazon rain forest. Researchers who once picked apart a single coral colony counted more than eight thousand burrowing creatures belonging to more than two hundred species. Using more sophisticated genetic-sequencing techniques, scientists recently looked to see how many species of crustaceans alone they could find. In one square metre at the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef, they came up with more than two hundred species—mostly crabs and shrimp—and in a similar-size stretch, at the southern end, they identified almost two hundred and thirty species. Extrapolating beyond crustaceans to fish and snails and sponges and octopuses and squid and sea squirts and on through the phyla, scientists estimate that reefs are home to at least a million and possibly as many as nine million species.

This diversity is even more remarkable in light of what might, to extend the urban metaphor, be called reefs’ environs. Tropical seas tend to be low in nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. Since most forms of life require nitrogen and phosphorus, tropical seas also tend to be barren; this explains why they’re often so marvellously clear. Ever since Darwin, scientists have been puzzled by how reefs support such richness under nutrient-poor conditions. The best explanation anyone has come up with is that on reefs—and here the metropolitan analogy starts to break down—all the residents enthusiastically recycle.

Because so much is at stake, Gates argues, the super-coral project is imperative. “I don’t really care about the ‘me’ in this,” she said one day over lunch in a strip mall in Kaneohe, the town closest to Moku o Lo‘e. “I care about what happens to corals. If I can do something that will help preserve them and perpetuate them into the future, I’m going to do everything I can.”

But scale is also what makes many other researchers leery of the project. Terry Hughes, the director of the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, once did a study of conventional coral-restoration projects, which involve raising coral colonies in tanks and transplanting them onto damaged reefs.

“I scoured the literature for any examples I could find,” he told me. He found some two hundred and fifty projects, which collectively cost a quarter of a billion dollars. The total area that was covered by the projects was just two and a half acres, or roughly two football fields.

“So we can call that the ‘restored area,’ though there are issues around that, because often the corals in these projects die,” Hughes went on. “When you consider just the Great Barrier Reef, which is a tiny fraction of the world’s reefs, it has the area of Finland. So going from a test tube or an aquarium to millions of football fields is hugely expensive, obviously.” The sort of scaling up that would be required would mean corals could no longer be transplanted; they’d have to be dispersed in another way, perhaps as embryos. (Coral embryos form larvae that drift around for a while before settling.)

“If you put corals—super corals—out in Kaneohe Bay, it would take probably thousands of years for them to spread naturally from Hawaii, which is an isolated archipelago,” Hughes said. “So you’d have to have some mechanism—aerial spraying from helicopters or something—to spread them around the Pacific. I don’t know how you would get to that next step.” At the time I spoke to Hughes, it was late summer in Australia, and the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef was suffering from the worst bleaching that observers had ever seen.

Ken Caldeira is a researcher at the Carnegie Institution for Science, at Stanford University, who studies ocean acidification. He noted that reef-building corals, from the order Scleractinia, have been around at least since the mid-Triassic. Yet reefs remain confined to those relatively few spots on the planet where conditions suit them just right.

“I find it implausible that we’re going to succeed in doing in a couple of years what evolution hasn’t succeeded at over the past few hundred million years,” Caldeira observed. “There’s this idea that there should be some easy techno-fix, if only we could be creative enough to find it. I guess I just don’t think that’s true.”

Half a hemisphere away from Moku o Lo‘e, the American Chestnut Research and Restoration Project operates out of several labs and a greenhouse in Syracuse, New York. It, too, might be described as an effort at assisted evolution, only with a much more radical assist. The project’s aim is not to breed up a tougher tree but to create one through genetic engineering.

William Powell, a professor at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, founded the chestnut project with a colleague, Charles Maynard, and now they co-direct it. Powell is fifty-nine, with gray hair, dark eyebrows, and a boyish earnestness.

“Not only was baby’s crib likely made of chestnut, but chances were, so was the old man’s coffin,” a plant pathologist named George Hepting wrote.

Then, in 1904, the chief forester at the New York Zoological Park—now the Bronx Zoo—noticed that some of the chestnut trees in the park were ailing. The following year, so many trees were turning brown that the forester appealed for help to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the New York Botanical Garden. Within five years, chestnut trees from Maryland to Connecticut were dying. The culprit was identified as a fungus, which had been imported from Asia, probably on Japanese chestnut trees, Castanea crenata. (Japanese chestnuts, which co-evolved with the fungus, find it only a minor irritant.) By the nineteen-forties, some four billion American chestnut trees had been wiped out. American chestnuts can resprout from the root collar; today, pretty much the only examples that still exist in the woods are small, spindly trees that have sprung up in this way.

“They will grow for a while and then get killed down to the ground again,” Powell told me. “So they’re kind of in what I call a Sisyphean cycle.” (The trees known as horse chestnuts, which can be found in many parks and gardens, are not, technically, chestnuts at all; they are members of a different family.)

Efforts to save Castanea dentata began almost as soon as the blight swept through. The first attempts involved hybridizing American chestnuts with other chestnut species. Then came zapping chestnuts with gamma radiation, in the hopes of producing a beneficial mutation. Next was a scheme to weaken the fungus by using a virus. These efforts produced thousands upon thousands of trees, all of which either succumbed to the blight or were so different from the American chestnut that they could hardly be said to be reviving it.

Powell attended graduate school in the nineteen-eighties, around the same time as Gates, and, like her, he was fascinated by molecular biology. When he got a job at the forestry school, in 1990, he started thinking about how new molecular techniques could be used to help the chestnut. Powell had studied how the fungus attacked the tree, and he knew that its key weapon was oxalic acid. (Many foods contain oxalic acid—it’s what gives spinach its bitter taste—but in high doses it’s also fatal to humans.) One day, he was leafing through abstracts of recent scientific papers when a finding popped out at him. Someone had inserted into a tomato plant a gene that produces oxalate oxidase, or OxO, an enzyme that breaks down oxalic acid.

“I thought, Wow, that would disarm the fungus,” he recalled.

Years of experimentation ensued. The gene can be found in many grain crops; Powell and his research team chose a version from wheat. First they inserted the wheat gene into poplar trees, because poplars are easy to work with. Then they had to figure out how to work with chestnut tissue, because no one had really done that before. Meanwhile, the gene couldn’t just be inserted on its own; it needed a “promoter,” which is a sort of genetic on-off switch. The first promoter Powell tried didn’t work. The trees—really tiny seedlings—didn’t produce enough OxO to fight off the fungus. “They just died more slowly,” Powell told me. The second promoter was also a dud. Finally, after two and a half decades, Powell succeeded in getting all the pieces in place. The result is a chestnut that is blight-resistant and—except for the presence of one wheat gene and one so-called “marker gene”—identical to the original Castanea dentata.

“I always say that it’s 99.9997-per-cent American chestnut,” he said.

In another plot, surrounded by an eight-foot fence, were a few dozen transgenic trees. These had smooth, unblemished bark, which reminded me of snakeskin. The tallest was about ten feet high and about six inches in diameter. It was a chilly day in March, and all the branches were bare. Powell explained that the fence was mostly to keep out deer, but also to discourage anti-G.M.O. protesters. He told me that I ought to come back in late spring, when the trees would be in bloom. Chestnuts produce streamer-like catkins, covered in tiny white flowers. “People used to say it was like snow in June,” he said.

Before any transgenic trees can be planted outside an experimental plot, they have to be approved by three federal agencies: the Department of Agriculture, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Powell is planning to request approval later this year. This will initiate a review process that could take up to five years. Once approval is granted—assuming that it is—Powell wants to produce ten thousand trees that can be made available to the public. If all these trees get planted and survive, they will represent .00025 per cent of the chestnuts that grew in America before the blight.

“This is a century-long project,” Powell said. “That’s why I tell people, ‘You’ve got to get your children, you’ve got to get your grandchildren involved in this.’ ”

As the world warms, and the oceans acidify, and species are reshuffled from one continent to another, it’s increasingly difficult to say what would count as conservation. In his most recent book, “Half-Earth,” the biologist E. O. Wilson argues that the best hope for the planet’s remaining species lies in leaving them alone. Even today, there are vast regions where, Wilson writes, “natural processes unfold in the absence of deliberate human intervention.” (The Amazon Basin is one such region; the Serengeti is another.) We ought to allow these processes to continue, Wilson argues. To this end, he recommends setting aside fifty per cent of the planet’s surface as reserves.

“Give the rest of Earth’s life a chance,” he pleads.

Those scientists who recommend this sort of hands-off approach—and there are many of them—stress the limits of what science can accomplish. Just because you can break an egg doesn’t mean you can put it back together. They argue that even the best-intentioned intervention can do more harm than good. People may read about a project like Gates’s or Powell’s and take exactly the wrong lesson from it.

“There’s a lot of psychology here,” Terry Hughes told me. “There is a danger of thinking we’ve found the technological solution, so therefore we can keep damaging reefs, because we can always fix them in the future.

“In terms of protecting ecosystems like coral reefs or rain forests, prevention is always better than cure,” he added.

Advocates for techniques like assisted evolution and genetic engineering argue that the moment for being hands off has passed. Humans have already so violently altered the world that without “deliberate intervention” the future holds only loss and more loss.

“There’s just too many people right now,” Powell told me. “I always say, ‘We need a full toolbox of methods to keep our forests healthy.’ And we shouldn’t limit it by saying, ‘Well, you can do this method but you can’t do that method.’

“You have emerald ash borer going through right now,” he went on. (The borer, another import from Asia, is killing ash trees from Colorado to New Hampshire.) “Should we just leave the ash trees and say, O.K., they’re gone? Woolly adelgid is killing the hemlocks. If we lose all the hemlocks, do we just say, O.K., that’s gone? There’s what’s called thousand-cankers disease that’s spreading on walnuts right now. Is that the kind of attitude we should have? We have all these challenges out there, and the question is: Should we just let the trees die out? And to me that’s not an option.”

When I was in Hawaii, I found myself wavering. I would listen to Gates and agree with her: there’s no going back. Then I would get on the little ferry and try to picture the super-coral project moving forward. My head would start to ache. Corals are slow to reach sexual maturity, and, when they do, most spawn only once a year. Crossbreeding requires many generations, and in that time—however long it may be—the seas will have grown that much warmer and more acidified. Well over a thousand species of Scleractinia have been identified, and probably lots more await discovery. To save reefs is a project akin to saving forests; one species of super coral wouldn’t be enough. You’d need to breed hundreds of them. And, even if this could be accomplished, how would you get billions and billions of polyps settled in the ocean?

“There are many, many unknowns,” she went on. “And people are very quick to criticize based on ‘But what happens if this doesn’t work and what happens if this doesn’t work?’ And I say, ‘Well, I don’t know now, but I know I’ll know more when I get there.’ And I feel that we’re at this point where we need to throw caution to the wind and just try.” ♦

[Editors Note: This article originally appeared in the Canton Repository on January 29, 2016]

January 29, 2016

Big things are happening behind the doors of an unremarkable white garage on the Walsh University campus.

A group of students launched the Garage — officially the Walsh University Innovation Center — this week. Housed in the back of the Katherine Drexel House, the innovation center gives students the space to turn their ideas into something tangible.

“We always said that ideas will die on paper. We really wanted to have a space where students can come together” and work on projects, said Matt Strobelt, a Walsh junior.

Strobelt, alongside fellow students Andrew Chwalik, Josh Ippolitio and Iagos Lucca, came up with the idea last fall. They pitched the idea to Walsh President Richard Jusseaume, who jumped on board. The project was funded by donors.

Before the Garage, there really wasn’t a space where students could get together and share creative ideas and problem solve, or even create new businesses, said Phil Kim, an assistant professor of business and the Garage’s faculty adviser.

Before it was transformed, the structure was filled with boxes, furniture and other odds and ends, said Chwalik, a senior.

Now the room, completely designed by students, exudes innovation: Three of the four walls are covered in dry-erase paint, power strips can be pulled down from the ceiling, and an electronic whiteboard and monitors allows for collaboration.

The name obviously comes from it being located in a physical garage, but also reflects a trait of business like Apple and Microsoft.

“Who doesn’t know a big name company that started in a garage?” Ippolitio said.

COMMUNITY

The Garage is more than just a gathering space; it also offers mentoring, networking and education opportunities.

They have a list of mentors, both Walsh alumni and members of the public, that can help students unsure of how to proceed with their project, Strobelt said.

They also hope to partner with local businesses on innovation challenges and host events such as Shark Tank watch parties, Ippolitio said.

On Thursday, the Garage hosted its first Blueprint Speaker Series presenter: Jim Cossler, CEO of the Youngstown Business Incubator.

The ongoing lecture series is another way to engage the community, inside and outside of the university, Chwalik said.

EXCITEMENT

Though its founders are business students, the Garage is open to everyone on campus.

Entrepreneurship isn’t limited to one school or major. Students from all backgrounds are valuable to the creative process and can foster collaboration, Kim said.

“We want all those students because that’s where rich ideas get even better. There’s a depth to it. They have perspectives that (business students) wouldn’t,” he said.

The Garage plans to develop online educational tools so those who haven’t taken certain classes can learn about marketing and business topics, Strobelt said.

“As much as we want this to be about the creating a business process, it’s also … going to be a learning process, so students can learn about general business sense,” he said.

On campus, excitement has been building about the project. The founders are often stopped by students who want to pitch ideas or ask questions.

“As we progressed into this project, it’s amazing to see that many of students actually had ideas, tons of ideas, and they’re ready to start putting the work in,” Lucca said.

They thought that finding interested students would be a challenge, and it has been, “but there’s a lot of people out there who have wonderful ideas who are ready to use the space. We’re very happy to see that,” he added.

The Garage has already seen its first business venture.

Last week, Chwalik officially launched ReTie (retiellc.com), an online shop for gently-used name brand ties.

“I’ve used the Garage already and it’s been a blessing so far,” he said. “I’ve had the resources and the space to make this dream a reality.”

‘Super Corals’ Could Survive Warming Oceans

(This article originally appeared on news.discovery.com on November 30, 2015)

By Lori Cuthbert

If you go to a tropical paradise this winter, you’ll likely snorkel on the local coral reef. If you do, take a good look, because those corals might not be around for much longer as warmer ocean temperatures kill them off.

That’s why one woman, Ruth Gates, Director of the Hawai’i Institute of Biology, is working on breeding “super corals” that can withstand the climate change that oceans are already experiencing.

Another group, in Australia, is creating “mutt” corals from different robust species to achieve the same result.

What’s unique about these approaches to coral preservation is that it’s like the land-based genetic tinkering that’s been done for millennia with livestock and crops.

“We’ve never taken a proactive and interventional approach” to saving corals, Gates told Discovery News at the University of Hawai’i’s Coconut Island research facility on O’ahu.

Land-based agricultural breeding methods “have never been used in the oceans,” she said.

But the method Gates uses is a bit different. She calls it “induced climatization” and “assisted evolution.”

With this method, and drawing on 25 years of coral research, she and her team of young researchers have just begun a program working with the five dominant species of corals in Hawai’i, in the heavily polluted Kaneohe Bay. Water temperatures on the reefs there can swing from 86 to 91 degrees Fahrenheit in a day, a change that can tax even the hardiest of corals.

Why go to such lengths to save coral reefs? “Three things: food, coastal security and tourism,” Gates said.

Coral reefs are home to 25 percent of marine species, according to the United Nations. 275 million people depend directly on reefs for survival and 850 million live within 62 miles of one.

Reefs protect shorelines from the effects of strong storms, breaking up wave energy that could wash away coastlines and the houses on them. As storms get stronger and more frequent with climate change, the security that reefs give coastlines will become even more important.

Coral reefs generate billions of tourism dollars worldwide; in Florida alone in 2000-2001, a four-county area in southeast Florida generated around $4.4 billion in local sales around their artificial and natural reefs.

And a report released earlier this year that compared Earth’s oceans to the world’s top 10 economies ranked them as the seventh largest, with $24 trillion in assets.

Coral Comeback

A 2014 bleaching event in Kaneohe Bay spiked water temperatures beyond what many corals could tolerate. When corals are too stressed, many will eject the tiny symbiotic algae that live on them and provide corals with many of their nutrients. The corals can die, leaving behind bleached-white skeletons.

As we snorkeled on the reef, spiky balls of ghostly-white, dead corals – some three feet or more in diameter — stood in stark contrast to their healthy cousins. Healthy corals are a deep, rich, greenish brown color.

Back on the research boat, Gates reported seeing up to 50 percent dead corals on the parts of the reef section where we snorkeled.

But there was something else. “Corals can come back after almost totally dying,” Gates said.

And, not all of the corals in the bay have been affected by bleaching or the frequent influx of pollution from the heavily populated shoreline.

Gates and her team theorized that if they could take some of these “super-performing” corals and push them to the limits of the heat, acidity and pollution they could withstand, then create offspring, the babies might end up with those same robust characteristics.

“How much stress do we have to give them before they develop a genetic memory for it?” Gates said.

“The hope is that, as parents, we can program our offspring to do better,” said Raphael Ritson-Williams, a post-doctoral student on Gates’ team. This is no different, he said.

The first round of the experiment formed the doctoral thesis of Hollie Putnam, an ocean scientist on Gates’ team who now runs that part of the program. The offspring of super corals were raised in the lab until, in 2014, they were big enough to go back out to the reef.

The results of that experiment were published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, Gates said.

“The first babies were transplanted back to the reef with zero percent mortality and survived the bleaching” event of 2014, Gates said. “It was a very significant result.”

More funding — $4 million from Microsoft’s Paul Allen’s Vulcan Foundation — arrived in June for the five-year program and Gates’ team is about to transplant more super coral babies to one of the reefs in Kaneohe Bay.

Gates acknowledges that her work is controversial to some scientists, who think she’s poo-pooing the approach of trying to mitigate climate change in favor of direct intervention.

But Steve Vollmer, Associate Director of the Marine Science Center at Northeastern University, isn’t one of them. “They are good first steps to understanding the potential for adaptation in corals,” he told Discovery News.

Gates said: “We should be doing everything we can, politically and practically.”

So what’s the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow for Gates?

“In each location, to have robust (coral) species that are always ahead of climate change,” she said. “But humans will always be involved. (Warming) is happening too quickly for corals to evolve on their own.”

http://news.discovery.com/earth/oceans/super-corals-could-survive-warming-oceans-1511301.html

When the Tea Party Met the Sea Party

[Editors Note: This article orginally appeared on the Huffington Post website on November 18, 2015]

By David Helvarg

So what do conservative Reps. Curt Clawson of Florida and Mark Sanford of South Carolina, liberal Rep. Sam Farr of California, climate activist Bill McKibben, a former petroleum engineer, an evangelical minister and a surfer all have in common? No, it’s not a joke. They all spoke out against offshore oil and gas drilling at a press conference earlier this month for the newly formed Sea Party Coalition. The Sea Party aims to make opposition to proposed offshore drilling a major issue in 2016.

President Obama’s decision two days later to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline after seven years of polarized debate, and the pushback it received, increases the likelihood that energy and the environment will play a prominent role in the upcoming election.

The president made his Keystone decision on a fossil-fuel project he inherited from his predecessor. It will likely be up to the next president to decide if the U.S. continues expanding the offshore oil and gas exploration that the Obama administration has proposed for both the Arctic Ocean (now on hold) and along the Atlantic coast.

Interestingly, the opposition to offshore drilling has a very different makeup than many past environmental battles. It’s as much about business, place and faith as it is traditional political alignments.

“I am proud to be a part of the growing Sea Party. As an Evangelical Christian, my biblical faith teaches me that God cares for his creation, so we should too,” said Virginia’s Rev. Richard Cizik, president of the New Evangelical Partnership for the Common Good. “I urge all candidates, from both sides of the aisle, to take a position on offshore drilling. It is a compelling challenge to the protection of our state’s coastline.”

The Sea Party’s press conference took place outside the U.S. Capitol next to an 85-foot life-size blue whale representing seas free of oil spills. To date, the Sea Party includes some 65 organizations ranging from environmental groups like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace to commercial fishing groups, aquaculture, surfers and small businesses.

The nature of the movement — coastal versus statehouse, Republicans and Democrats aligned on both sides — may also have unpredictable impacts on states slated for offshore drilling such as Florida, Virginia and South Carolina, increasing the likelihood that the presidential candidates will have to take a position in 2016.

Every coastal town and city in South Carolina, for example, arguably one of the most conservative states in the union, has passed resolutions against offshore oil surveying and drilling.

Rep. Mark Sanford, whose district includes much of South Carolina’s coast, told the Sea Party gathering, “It’s important that people get their voices heard. Think about all the towns and hamlets in South Carolina coming together as communities to say this is not a good idea. What we’re really talking about is upholding the democratic tradition our founding fathers gave us 200 years ago.” After the press conference South Carolina’s largest newspaper, Charleston’s Courier and Post, ran a column titled “Mark Sanford From Tea Party to Sea Party,” noting how elements of the left and right are working together to stop the drilling.

Sanford complimented Peg Howell of Pawleys Island, South Carolina, at the press conference. Howell is a former petroleum engineer who was once a supervising “Company Man” on Chevron rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. “Working on a drilling rig is one of the riskiest things I’ve done in my life and drilling is done by some of the most highly trained personnel in the world,” she explained. “But people make mistakes and spills happen — not only on the rigs, but also from on-shore processing facilities, pipelines, tankers and rail cars.” She went on to warn that the economic benefits of drilling being promoted by the oil industry are vastly overrated, especially given the risk drilling poses to existing coastal businesses.

“People come to Monterey to see whales, not oil rigs,” Rep. Sam Farr of Monterey, California, agreed. “We’re the whale-watching capital of the world. People are making billions of dollars [in tourism] and the tourist dollar is a sustainable dollar, where the high-risk low gain oil dollar is not. Now we’re here in Washington, D.C., starting this new movement, the Sea Party. I’m a member and I say expanding offshore drilling will only increase the number of spills and increase our dependence on fossil fuels. We can’t drill and spill our way to a healthy ocean and the blue economy that it supports.”

From across the aisle Rep. Curt Clawson, who represents another coastal district on Florida’s Gulf of Mexico, sounded a similar refrain, “I love the ocean, I love the Gulf and I want to conserve it … which includes stopping drilling in the Gulf. Fish don’t like oil spills and neither do I.”

Clawson, one of the most conservative members of the House, then told a reporter from the News Press, a newspaper covering Southwest Florida, that, “There’s an intersection with economic health and growth. It’s an ecology issue, a lifestyle issue and an economic issue. Destroying the Gulf is not good on any level.”

Others among the Sea Party speakers included Bill McKibben, a key leader in the battle against the Keystone pipeline, a sea turtle rehabilitator from North Carolina, a spokesman from the Great Whale Conservancy, an acoustics expert from California who played whale vocalizations while explaining the risk to marine wildlife from loud and repetitive noise generated by oil industry acoustic survey ships, and environmental and ocean directors for Greenpeace, the Surfrider Foundation and the Ocean Foundation.

For the remainder of the year, the Sea Party will likely be responding to what comes out of the Paris Climate Summit. In the wake of last week’s tragedy in the city of light, the hope is that world’s leaders will commit to moving away from our collective addiction to oil that is both funding terrorism and destroying the planet.

In 2016 the Sea Party plans to focus its attention on southeastern states between Delaware and Florida, where new federal oil leases have been proposed while also taking its message national. Its aim will be to grow the anti-offshore oil drilling opposition, promote clean renewable energy and do voter education on ocean conservation, “to restore the blue in our red, white and blue.”

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-helvarg/when-the-tea-party-met-the-sea_b_8585988.html

How we are all contributing to the destruction of coral reefs: Sunscreen

[Editors Note: This article originally appeared in the Washington Post on October 20, 2015]

By Darryl Fears

The sunscreen that snorkelers, beachgoers and children romping in the waves lather on for protection is killing coral and reefs around the globe. And a new study finds that a single drop in a small area is all it takes for the chemicals in the lotion to mount an attack.

The study, released Tuesday, was conducted in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Hawaii several years after a chance encounter between a group of researchers on one of the Caribbean beaches, Trunk Bay, and a vendor waiting for the day’s invasion of tourists. Just wait to see what they’d leave behind, he told the scientists – “a long oil slick.” His comment sparked the idea for the research.

Not only did the study determine that a tiny amount of sunscreen is all it takes to begin damaging the delicate corals — the equivalent of a drop of water in a half-dozen Olympic-sized swimming pools — it documented three different ways that the ingredient oxybenzone breaks the coral down, robbing it of life-giving nutrients and turning it ghostly white.

Yet beach crowds aren’t the only people who add to the demise of the coral reefs found just off shore. Athletes who slather sunscreen on before a run, mothers who coat their children before outdoor play and people trying to catch some rays in the park all come home and wash it off.

Cities such as Ocean City, Md., and Fort Lauderdale, Fla., have built sewer outfalls that jettison tainted wastewater away from public beaches, sending personal care products with a cocktail of chemicals into the ocean. On top of that, sewer overflows during heavy rains spew millions of tons of waste mixed with stormwater into rivers and streams. Like sunscreen lotions, products like birth-control pills contain chemicals that are endocrine disruptors and alter the way organisms grow. Those are among the main suspects in an investigation into why male fish such as bass are developing female organs.

Research for the new study was conducted only on the two islands. But across the world each year, up to 14,000 tons of sunscreen lotions are discharged into coral reef, and much of it “contains between 1 and 10 percent oxybenzone,” the authors said. They estimate that places at least 10 percent of reefs at risk of high exposure, judging from how reefs are located in popular tourism areas.

“The most direct evidence we have is from beaches with a large amount of people in the water,” said John Fauth, an associate professor of biology at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. “But another way is through the wastewater streams. People come inside and step into the shower. People forget it goes somewhere.”

The study was published Tuesday in the journal Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Fauth co-authored the study with Craig Downs of the nonprofit Haereticus Environmental Laboratory in Clifford, Va., and Esti Kramarsky-Winter, a researcher in the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University in Israel.

Their findings follow a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study two weeks ago that said the world is in the midst of a third global coral bleaching event. It warned that pollution is undermining the health of coral, rendering it unable to resist bleaching or recover from the effects.

“The use of oxybenzone-containing products needs to be seriously deliberated in islands and areas where coral reef conservation is a critical issue,” Downs said. “We have lost at least 80 percent of the coral reefs in the Caribbean. Any small effort to reduce oxybenzone pollution could mean that a coral reef survives a long, hot summer, or that a degraded area recovers.”

Coral reefs are more than just exotic displays of color on the sea bed. The National Marine Fisheries Service, a division of the NOAA, placed their value for U.S. fisheries at $100 million. They spawn the fish humans eat and protect miles of coast from storm surge.

“Local economies also receive billions of dollars from visitors to reefs through diving tours, recreational fishing trips, hotels, restaurants, and other businesses based near reef ecosystems,” NOAA said on its Web site. “Globally, coral reefs provide a net benefit of $9.6 billion each year from tourism and recreation revenues, and $5.7 billion per year from fisheries.”

Oxybenzone is mixed in more than 3,500 sunscreen products worldwide, including popular brands such as Coppertone, Baby Blanket Faces, L’Oreal Paris, Hawaiian Tropic and Banana Boat. Adverse effects on coral started on with concentrations as low as 62 parts per trillion. There are alternative sunscreens with no oxybenzone, including a product called Badger Natural Sunscreen and dozens of others on a list provided by the non-profit Environmental Working Group.

Measurements of oxybenzone in seawater within coral reefs in Hawaii and the U.S. Virgin Islands found concentrations ranging from 800 parts per trillion to 1.4 parts per million,” according to the authors. That’s 12 times the concentrations needed to harm coral.

“This study raises our awareness of a seldom-realized threat to the health of our reef life … chemicals in the sunscreen products visitors and residents wear are toxic to young corals,” said Pat Lindquist, executive director of the Napili Bay and Beach Foundation in Maui. “This knowledge is critical to us as we consider actions to mitigate threats or improve on current practices.”

http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2015/10/20/after-sunscreen-protects-humans-it-massacres-coral-reefs/

Hawaii to experience worst-ever coral bleaching due to high ocean temperatures

[Editor’s Note: Dr. Ruth Gates is involved in a Herbert W. Hoover Foundation funded initiative to use evidence-based research to measure the coastal health of areas around the world.]

HONOLULU (AP) — Warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures around Hawaii this year will likely lead to the worst coral bleaching the islands have ever seen, scientists said Friday.

Many corals are only just recovering from last year’s bleaching, which occurs when warm waters prompt coral to expel the algae they rely on for food, said Ruth Gates, the director of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. The phenomenon is called bleaching because coral lose their color when they push out algae.

The island chain experienced a mass bleaching event in 1996, and another one last year. This year, ocean temperatures around Hawaii are about 3 to 6 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than normal, said Chris Brenchley, meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Honolulu.

Bleaching makes coral more susceptible to disease and increases the risk they will die. This is a troubling for fish and other species that spawn and live in coral reefs. It’s also a concern for Hawaii’s tourism-dependent economy because many travelers come to the islands to enjoy marine life.

Gates compared dead coral reef to a city laid to rubble.

“You go from a vibrant, three-dimensional structure teeming with life, teeming with color, to a flat pavement that’s covered with brown or green algae,” said Gates. “That is a really doom-and-gloom outcome but that is the reality that we face with extremely severe bleaching events.”

Gates said 30 to 40 percent of the world’s reefs have died from bleaching events over the years. Hawaii’s reefs generally have been spared such large scale die-offs until now. Most corals bleached last year bounced back, for example. But Gates said it will be harder for these corals to tolerate the warmer temperatures two years in a row.

“You can’t stress an individual, an organism, once and then hit it again very, very quickly and hope they will recover as quickly,” she said.

Scientists have reports of bleaching in Kaneohe Bay and Waimanalo on Oahu and Olowalu on Maui. For the Big Island, reports of bleaching have come in from Kawaihae to South Kona on the leeward side and Kapoho in the southeast.

Scientists on an expedition to the remote, mostly uninhabited islands in the far northwestern end of the island chain reported some coral died after last year’s bleaching event. Courtney Couch, a researcher at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, said a mile and a half of reef on the eastern side of Lisianski Island was essentially dead. Coral further out from the atoll handled the warm temperatures better, she said.

Brian Neilson, an aquatic biologist with the state Department of Land and Natural Resources, said people could help by not adding to the coral’s problems.

That means avoiding fertilizing lawns and washing cars with soap so contaminants don’t flow into the ocean. People should avoid walking on coral and boaters should make sure they don’t drop anchor on coral. Fishermen should fish responsibly, he said.

Scientists have also asked people to help them keep track of bleached coral by reporting sightings to the state’s “Eyes on the Reef” website at www.eorhawaii.org.

Brenchley, from the National Weather Service, said it’s not known why waters around Hawaii and other parts of the northeast Pacific are warmer than normal this year. This warm water — nicknamed “The Blob” — is coinciding with El Nino, which is a general warming of parts of the Pacific that changes weather worldwide. But Brenchley said it isn’t the result of El Nino.

Hawaii is home to 85 percent of the coral under U.S. jurisdiction, including 69 percent within the mostly uninhabited islands of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument. Another 15 percent of U.S. coral lies among the Main Hawaiian Islands — from Niihau in the north to the Big Island in the south — where the state’s 1.4 million people live.

Policing Seafood with DNA

[Editors Note: This article highlights work that is being funded through the Herbert W. Hoover Foundation]

By Ben Shouse and Scott Baker

“Fishy”—meaning inspiring doubt or suspicion—is a fairly apt description of the way in which much of the world’s fish is bought and sold these days. Peer-reviewed research suggests that as much as a quarter of the seafood on the market is not even labeled as the correct species, making fraud one of the biggest problems in the seafood industry.

A second, related problem is that roughly a quarter of wild-caught seafood is hauled in using questionable or even blatantly illegal practices, including the use of kidnapping and forced labor on fishing vessels. This illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing can deplete marine populations, threatening food security in the developing world and resulting in $10 billion to $23 billion in economic losses globally each year. Here in the U.S., illegal imports represent about 25 percent of all wild-caught imports and are worth $1 billion to $2 billion annually.

In March, an Obama administration task force released an ambitious plan to confront seafood fraud and illegal fishing. The plan calls for large-scale tools, such as satellites to watch suspicious vessels and an international agreement to close the world’s ports to fish caught illegally. But the task force should also look seriously at investing in genomic methods that allow the simultaneous study of multiple genes. Genomics and other molecule-level tools have great potential to improve seafood traceability and to better protect consumers and law-abiding players in the fishing industry.

Species identification is routine and reliable using a few hundred letters of the four-letter DNA code (often a section of mitochondrial DNA known as the “bar code”). U.S. agencies have been using this process to detect seafood fraud for years, but on only a small fraction of the market, and researchers around the world have been documenting IUU fishing and illegal whaling for more than two decades. For example, sequencing of several hundred samples from retail markets in Japan and South Korea has documented illegal hunting of humpback and gray whales. And one sample from a sushi restaurant in Santa Monica, California, was identified as an endangered sei whale. Similar work is underway to document the prevalence of protected shark species in Hong Kong markets.

The crew of the Bangun Perkasa, a stateless fishing vessel suspected of illegal large-scale high-seas drift net fishing, tend their fishing nets prior to a Coast Guard law enforcement boarding conducted by the Kodiak-based Coast Guard Cutter Munro Sept. 7, 2011. The U.S. Coast Guard actively participates in the international cooperative efforts against large-scale high-seas drift net fishing as encouraged by the United Nations moratorium. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Coast Guard Cutter Munro)

While these efforts involved decoding only small segments of DNA, reading longer stretches could offer deeper insight. Until recently, the necessary technology was expensive, slow, and not readily usable in the field, but the cost of sequencing has dropped 10,000-fold in the past eight years, and the speed has more than doubled each year, exceeding Moore’s law. This offers new opportunities to scale up and accelerate the targeted testing the U.S. already does for seafood fraud. Perhaps more importantly, it offers numerous ways to combat IUU fishing by revealing where fish are being caught and potentially enabling investigators to find DNA evidence aboard fishing vessels.

One key step in the expansion of this technology is the rollout of fast, handheld devices for detecting seafood fraud and IUU fishing. The models that are currently available offer only yes-or-no identification of commonly mislabeled fish such as grouper. They use short, custom-synthesized DNA sequences that produce a fluorescent signal when a sample is authentic. Adoption of such tools could allow authorities to detect mislabeled fish on site, confiscate those shipments, and quickly start an investigation. (This would be even easier if seafood labels had to include the scientific name for each species.)

However, to be more useful against IUU fishing, these devices will need to go beyond yes-or-no results and instead read the letters of the DNA code. One promising technology is a “nanopore” sequencer—a handheld device that plugs into a laptop, pulls a DNA strand through a very small hole, and reads it using electronic sensors. Today’s devices have an error rate of up to 30 percent, but improvements are coming.

WESTERN PACIFIC OCEAN (Oct. 29, 2014) A small boat team of Sailors and Coast Guardsmen embarked aboard the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Michael Murphy (DDG 112) prepare to board a fishing vessel to conduct an inspection as part of the Oceania Maritime Security Initiative (OMSI), a bilateral agreement to provide patrols within the Central Pacific for illegal fishing and other transnational crimes. Michael Murphy is on deployment to the 7th Fleet area of responsibility supporting security and stability in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy Photo/Released)

Handheld sequencing technology would make it possible to scan several thousand letters of chromosomal DNA to find single-letter variations. This technique can be used to identify species and, in many cases, trace the sample to the population of origin. This information can be enough to show that a fish was caught illegally, or at least that its shipping label is not accurate. A study in Europe used these single-nucleotide polymorphisms to differentiate cod specimens from three populations—the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and Northeast Atlantic Ocean—with 95 percent accuracy. The Marine Stewardship Council, a prominent organization that labels sustainable seafood, is considering using these findings to withhold its seal of approval from cod caught in regions with low abundance.

The tools are available today to do the same thing for Pacific salmon, and the U.S. could fund research to develop the necessary data for other species on which IUU fishing is suspected, such as bluefin tuna or Patagonian toothfish (marketed as Chilean sea bass). Alternatively, the U.S. government could target specific locations where IUU fishing is known to occur and then use DNA to identify shipments from those places.

One final intriguing possibility is identifying traces of DNA from illegally caught fish on the decks and in the nets or freezers of fishing boats, even after the contraband has been offloaded. One simple method would be to run water over the deck or hold of a vessel and test it for environmental DNA (eDNA)—material left behind from the shedding of scales and other tissue. This information could be checked against the ship’s manifest, alerting authorities to IUU fishing—especially on the high seas, where conventional observation and inspection are difficult.

Genomics is not the only tool needed to combat fisheries crime. By itself, it can’t tell you if someone is exceeding a quota or using illegal gear. Further, some genomic technology is not yet practical or reliable. The tools we have now, however, are more than sufficient to greatly improve our confidence in the identity of the fish we eat, to give fishermen fairer markets for their catch, and to make a critical food source more sustainable.

Reposted from http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/policing-seafood-with-dna/

That wild caught shrimp you just ate? It might be from a skanky, destructive farm

(Reprint from http://theseamonster.net/2015/08/shrimp_fraud/)

Like lots of people, you probably love shrimp. Love to eat them that is. And hopefully you know, shrimp farming is highly destructive. To make a shrimp farm, you first clear out all the mangroves, destroying a critical coastal ecosystem. Mangrove loss results in greater storm and tsunami impacts, greatly reduced fisheries production (mangrove roots, below the water, act as fish nurseries), and also reduced carbon sequestration. BIG BUMMER. So you do the right thing and only buy wild caught shrimp. Moreover, you want to supper local fisherman, like the families that have been shrimping in our vast estuaries here in North Carolina for decades. But how do you know what you buy isn’t actually coming from a polluted, destructive shrimp farm in Thailand? You don’t.

You are at the mercy of the vendor. Yet many seafood vendors don’t know where their product comes from or they are just dishonest about it. A NC food processor (why do we even have “food processors”?) was just busted for mislabeling shrimp:

Federal prosecutors say a Dunn-based seafood processor and distributor used a bit of bait-and-switch when falsely labeling almost 25,000 pounds of farm-raised imported shrimp headed for Louisiana. source

Beyond this, wild caught shrimp is generally highly environmentally destructive too. Usually, shrimp are caught by dragging huge nets across the bottom. This destroys habitat too (like seagrass beds) and also kills countless other critters that get scooped up and die as bycatch. More on that later…